September 6, 2011

Day 1 of my CRS trip to Africa. Arrival in Baltimore: I learned today I have something in common with a brutal dictator, namely Muammar Gaddafi. We both are apparently headed to Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Burkina Faso. Most of us have never heard of it. Until today. It’s blaring from the radio this morning, the day of my departure. So much for my visit to a sleepy African nation, whose name means “land of people with integrity,” and which the Culture Gram describes as a warm, friendly, and generous nation where people are respected for the ability to control one’s tongue. Oh well, I’ve always enjoyed military airshows … just not looking forward to a flyover accompanied by strafing and laser-guided bombs.

Day 2

Security briefing things to remember: Keep a local handy. Don’t stray. The crocodiles won’t harm you, as long as you keep your distance. Be careful when walking along roadsides; you never know when a vehicle might blow a tire, swerve, and take you out. Bathrooms are sanitary”ish.” And CRS has never lost anybody. Misplaced, maybe, but permanently lost… never. It’s nice to know CRS has a highly refined alert system with technical designations for each of the 5 levels. My favorite because of familiarity is Level 5 – Hunker Down. In south Louisiana, we know a lot about hurricane hunkering. It’s comforting to know there’s an international vocabulary when disaster strikes.

As for the purpose of my trip … Catholic Relief Services invited me on this as part of its Global Solidarity Initiative to experience our Faith Community in Action. We’ll visit sites rescuing child brides and persecuted women accused of witchcraft. As someone once said, hope lies in our ability to be disturbed. I am reminded both that concern for the poor is rooted in our Christian Faith and embedded in our governing tradition dating back to the laws of ancient Israel. We should be disturbed, these days. In listening, I am reminded of a conversation with my daughter after she recently returned from a month in Kenya, where she lived in a tent in the bush teaching children of the nomadic Massai tribe. Eventually, she said she learned to forget everything that she thought she knew. After that, her experiences were able to penetrate. Wise words from a 20-year-old. Isn’t an abandonment of self the beginning of an authentic spiritual journey? As one of my colleagues said about this trip, she is looking forward to getting to know the world differently.

Next stop: Ouagadougou (wah ga doo goo, rhymes with puldoo, I suppose for all you coot fans out there) rumored destination of my BFF Qadaffi. But actually, my best chances of catching up with him maybe the layover in Niger. Some of his troops have been spotted nearby. If we miss each other, I am told we may meet some “supernuns” at other stops during our journey. Supernuns vs. Kadafi…hmmm, at least I know how to spell Supernun, should I meet one.

September 7, 2011

Our “equipment” was rerouted to Montreal due to weather. So out of an abundance of caution, we decided the wise course of action would be to top off the fluids of our reserve engines. That’s Boss Lady Kim in the background. I am growing concerned that I may miss my appointment with Kadaffi.

September 8, 2011

Solidarity stinks. Flying Air France across the Atlantic to Africa, to a part of the world populated with people where food insecurity (pause and think about that!) characterizes their daily lives, my five-course meal pleases me. Global solidarity with the poor, who needs it? After two days of travel delays, the prelude of quail with chestnuts and cranberry was well deserved and preceded by choice of wines which in turn were introduced by a warm towel infused with mint,* all served by a French gentleman who tucks one arm behind his back and bows whenever he approaches. This is a Seinfeldian moment. After the equipment delay at Dulles, I was upgraded. Tah Dah! I’m sitting in a seat that has at least 81 combinations of adjustments while a dozen of my colleagues quietly suffer on the other side of the curtain. But I choose not to think about them. Why bother.

Then I remind myself: excess is the enemy. Some of us fly high while others slog through the muck.

That, however, is the issue: self-righteousness, which after all obscures the original problem, judgment. Thinking we know. Victor Frankl probably said it best to us westerners, although the insight is the basis of many world religions. We can’t always choose our circumstances, but we can choose our response. That is the core of our freedom, and it’s the core of an ascendant spiritual journey. Gratitude, appreciation, thankfulness. Responding with an open heart in a manner that binds, instead of one that divides. Corny perhaps, but WWJD drifts into my thoughts. Accept. Be thankful, and realize that our shared destination is linked to others, whether the other speak politely in French, and regardless of the other is on the other side of the curtain, the other side of the world, the other side of the tracks in your hometown, or the other room in your house.

*I should fess up. While the couple next to me daintily dabbed fingertips, I swabbed my face, neck, and behind my ears. After racing through the airport when I realized I had lost my entry papers (which I found at the security screening station) I had had my share of sweaty moments today. Thankfully, before I could regret it, the interior voice of what would have been my justifiably embarrassed teenage daughter stopped me short of diving under my collar. But I kept the towel …

Air France First class menu: L’amuse-bouche, quail with chestnuts and cranberry preserves, pictured in the spoon. The plate … a/k/a L’entree Gourmande … Smoked breast of duck, scallop flan with tarragon, and basil mayonnaise.

Day 4:

“I’m just a girl. I wasn’t ready to marry an old man I had never seen before.” So this 14-year-old girl ran. She ran from her family and village, from all she had ever known to the only safety she knew, Centre des Jeunes Filles–a community of nuns in this west-African country of Burkina Faso. In the city of Kaya, she found refuge and now shares a dirt-floor existence with young girls escaping forced marriages. But although she avoided one immediate threat that would have given her a certain known future, her future now is clouded with uncertainty.

These homes for women and girls are scattered throughout this nation, most – if not all – run by Catholic nuns on meager resources. Sr. Georgette Sawadogo says that hunger pains them daily. And although it will take generations to change centuries of tribal customs, hunger can have a quick fix. This is where the support of the American Catholic church through Catholic Relief Services has made a difference. A few years ago, CRS constructed buildings the girls now use to raise pigs. The pigs provide not only food but a marketable product to help the center raise money.

On the day that we visited the center, I am struck by those things that seem like bits of teenage life  from Baton Rouge. Maria, for example, has her hair braided in purple and gold like if she’s ready for an LSU home game. The girls laugh and giggle and cluster closely, just like a group of girls you’d come across at a CHS football game. They brought out cloth they had woven and painted, and for about 30 minutes the girls and the women in our group acted like…. well, acted just like you’d expect them if they were your daughters, sisters, aunts and mothers, friend and family. Fashion has no language barrier.

from Baton Rouge. Maria, for example, has her hair braided in purple and gold like if she’s ready for an LSU home game. The girls laugh and giggle and cluster closely, just like a group of girls you’d come across at a CHS football game. They brought out cloth they had woven and painted, and for about 30 minutes the girls and the women in our group acted like…. well, acted just like you’d expect them if they were your daughters, sisters, aunts and mothers, friend and family. Fashion has no language barrier.

Sr. Georgette explains that while at the center, they may design and make fabrics, but there is little future in that for these girls. In a global economy, street vendors sell more cheap cloth imported from China. The nuns lack resources to prepare young women for independence and economic security in an interconnected world.

The center’s ultimate goal is to reunite the girls with their families, but it takes time to heal the wounds of humiliation that both the girls and their families have suffered. Sometimes it doesn’t go as planned either. Fistfights have broken out, and they’ve had to force parents to leave the compound. As our time draws to an end, and after hearing about – and seeing — their struggle to survive, their last act of grace gifted to us was a song giving praise and glory to God for all the good entering their lives.

Day 5

It’s a long story, but we went to look at rice fields but walked away with two live chickens and dozens of hard-boiled guinea eggs. It started in 2009, with a devastating flood the likes of which were unimaginable. But comfort in the unlikely was short-lived. In 2010, the floodwaters rose higher.

Enter Catholic Relief Services. While the first image many of us have about our support for CRS may be humanitarian aid following a disaster, perhaps their most significant impact will be not from immediate relief, but from projects aimed at long-term change. CRS responded to the floods with a comprehensive, intertwined, and mutually supportive set of services. Tents and food for immediate relief. Food vouchers for intermediate recovery, and then aiming at future generations — housing replacement (not reconstruction) and the introduction of new agricultural techniques and crops.

And when CRS responds for the long-haul, their projects provide incentives for change rather than a system of dependency or a return to the status quo.

When Burkina Faso received nearly half of its annual rainfall in a few days, mud-brick houses floated away. Problem: Rebuild vulnerable structures, or improve and replace? CRS pursued the latter, but not without a demonstrable commitment to improving on the part of a family. CRS provided concrete and concrete blocks for a solid foundation. But a family only received this material after it had secured bricks, windows, and other products necessary to complete a house.

When Burkina Faso received nearly half of its annual rainfall in a few days, mud-brick houses floated away. Problem: Rebuild vulnerable structures, or improve and replace? CRS pursued the latter, but not without a demonstrable commitment to improving on the part of a family. CRS provided concrete and concrete blocks for a solid foundation. But a family only received this material after it had secured bricks, windows, and other products necessary to complete a house.

In Burkina Faso, food insecurity characterizes daily life. So, when helping farmers replant after the flood, CRS worked with USAID to introduce rice farming to a low-lying area. Although the first crop is yet to be harvested, the hope is that rice yield will produce more nutrition per acre on each family’s plot than the traditional grains of sorghum and millet.

As for the chickens… everywhere we go, entire villages turn out to greet us. So after walking the hand-built ridges separating the rice fields, through their chief, the village of Wattigue, gave thanks to God for all the good things in life and then presented us with two chickens, immobilized by a cloth strip tied around their legs. I know a good thing when I see one, and so the Cajun in me was ready to pluck and smother, but cooler heads prevailed. We donated the chickens to the Centre des Jeunes Filles, where we had visited the day before. The eggs came from a village where CRS is assisting in rebuilding homes.

For a people where hunger is a daily reality, and women show you their children’s distended stomachs and ask for advice, it is a humbling experience. It’s the parable of the widow’s mite; you’re never too poor to not live generously.

September 14–Crossing the border into Mali

At dusk we crossed the border into Mali, a sandstorm crossing our path as torrential rain poured from the sky. It was like driving through red mud soup. The dirt road we followed was unlit, except for the passing glow of headlights hardly able to penetrate the muck. And the lighting. The outlines of the African plains flickered in all directions for two hours as we thumped and bumped our way into Mali, twelve of us packed into our minibus, a Toyota Hiace. They tell me that outside, the shadow landscape resembles the American Southwest. We left Burkina Faso after visiting a center for women accused of witchcraft and banished from their villages; treated like lepers living separate and apart for the rest of their lives. I’ll write about that at our next stop.

September 17

This has been the most troubling of our group’s stops. How can I write about Clementine? She’s been branded a sorcerer, banished forever from her village. Rejected by her family. Never to see her children again. Now an outcast in Ouagadougou, but for her community of women accused of the same and a small group of Catholic nuns.

Although the people of Burkina Faso are largely Catholic and Muslim, traditional spirituality mixes into their village life. When catastrophe strikes, such as the death of a young child (old people are supposed to die, not children) a village will sometimes scapegoat a woman; blame her for practicing witchcraft and stealing the soul of a child. The woman is often beaten, her house burned and she is run out of the village.

At the Centre, the women get a room and access to the tools they need to continue their subsistence lifestyle, which is The Lifestyle of this country. Walking through the Centre is like being inside an ant colony; you are surrounded by a constant scurry of activity. Women are spinning thread, working in gardens, chopping wood, and thrashing grain. Smoke drifts and the smell of cooking fires hovers in the air.

The Centre currently is home to about 300 women, down about 125 from its highest numbers a few years ago. Catholic Relief Services, the Burkina Faso government, and the tribal leadership have been fighting against it with education, information, and advocacy – holding protest marches, for example. Progress takes tiny steps; the children of a woman may contribute to her care, but not see her. Other family members may come for an occasional visit.

CRS works on two fronts, helping to support the Centre’s operational costs, but also working to change the cultural norm through its Peace and Justice Commission, which works with both the government and traditional tribal leadership.

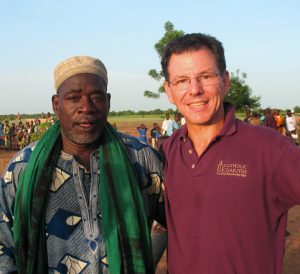

The slow pace of progress bothers me. I can’t help but wonder: Why?. Why send our resources half-way around the world to such a seemingly backward people. But then, I meet Hamado Zore, a farmer in the Province of Nanmatenga. One of his daughters snuggles up to him while he talks about his love for his children with a smile and the same fondness I see in my own family, in the love my brothers express for their children.

The slow pace of progress bothers me. I can’t help but wonder: Why?. Why send our resources half-way around the world to such a seemingly backward people. But then, I meet Hamado Zore, a farmer in the Province of Nanmatenga. One of his daughters snuggles up to him while he talks about his love for his children with a smile and the same fondness I see in my own family, in the love my brothers express for their children.

In Baton Rouge, Catholic Charities staff is preparing for an event at our Sanctuary for Life, and I am reminded we too banish women. Our Sanctuary is a home for women who find themselves pregnant, alone, and unsupported – sometimes unwanted and kicked out by their family. They have no place else to go. Shame on Burkina? No, shame on us.

We really aren’t as different after all.

September 18, 2011

A drop of water rose to the surface of Minta and rippled waves of change for every family in the village. Less thirst and less disease mean “there are fewer tears in our village. Our children don’t cry as much,” a woman told us as we gathered in the village center.

Gathering at the village center, however, was quite an adventure. After one hour on blacktop then a dirt road, I was about to find out that there are dirt roads and then there’s … dirt. We literally turned off through a millet field and wound our way through mile after mile of millet following a bumpy twisting trail, between mud brick-walled homes of villages, across rice paddies, and in the process lost our large van when the ruts proved too deep. So we decided to try out our clown act; 17 of us piled into 3 small SUVs and a pickup truck. Not everyone had a seat.

It was worth the effort. The entire village of Minta had turned out to greet us in song and dance at the village center. After the celebration, we gathered under a shelter made of logs and branches and villagers told us how their life has improved since Catholic Relief Services installed a pump and water tower to bring water to the village center from a well dug by other global agencies. Clean water – and the sanitation initiative that accompanied it – has transformed village life. You can see it in the faces of the children. Compared to another village we had visited yesterday, their skin is cleaner. There are fewer runny noses, gooey eyes …. and circling flies.

It was worth the effort. The entire village of Minta had turned out to greet us in song and dance at the village center. After the celebration, we gathered under a shelter made of logs and branches and villagers told us how their life has improved since Catholic Relief Services installed a pump and water tower to bring water to the village center from a well dug by other global agencies. Clean water – and the sanitation initiative that accompanied it – has transformed village life. You can see it in the faces of the children. Compared to another village we had visited yesterday, their skin is cleaner. There are fewer runny noses, gooey eyes …. and circling flies.

Villagers also contribute to maintenance and upkeep. The faucet is tended and each villager has to pay about 5 cents when filling up the 5-gallon containers that supply water at each home. A quick drink is free. The money will be saved to use for future maintenance. (In another village, to enforce sanitation policies, people must remove their shoes when walking onto the slab that holds the faucet or pay a 10-cent fine.)

The effects of this combined water and sanitation project reach beyond material improvement, partially contributing to increased school attendance by girls. Gender roles are fairly rigid in the village. Mothers and daughters are responsible for the household; fathers and sons for tending cattle and sheep. If a woman has to spend less time hauling water, then she has more time to work in the home, and needs less help from daughters, giving their daughters more time for school. A spectacle awaited our arrival at Toumadiama. A greeting line. Drums. Music. And dancing in the village square. Men in one corner. Boys in another, and women in the center. Where ever we go, women stand out in their exotic colorful cloth, head wraps, and especially the intensity of their labor.

This entire continent seems to have been cultivated by women, stooped over and swinging a 3-inch-bladed hand tool. They are ubiquitous. Ubiquitous yet invisible. “Our women live in obscurity,” a man in the Village tells us inside a classroom while outside the scene looks the same as thousands of years ago: teenaged boys tend cattle and sheep at a watering hole, young boys roll hoops along dirt trails, and women walk across the savannah hauling bundles balanced high on their heads with infants strapped to the small of their backs.

Ubiquitous and obscure simultaneously, like Africa itself. It makes sense, then, that enlightened village leaders, i.e., men, welcome programs from Catholic Relief Services that improve opportunities for women. How is this done?

The rice-farming initiative in Wattigue was implemented after the village agreed to allow women heads of household to participate as owners of their crops. The result: A mother of five should have enough rice to feed her children with some leftover to sell for income.

Food is distributed to families by schools, and only through female students who have a minimum attendance rate of 80%. The result: girls’ attendance at a school Minta doubled, from one girl for every two boys to an even ratio.

Women participate in the start-up of village credit unions/lending communities and are eligible to receive loans. The result: In the village of Toumadiama, a mother bought seeds with a loan of 10,000 CFA francs and earned more than 100,000 francs by selling the okra, peanuts, and beans she planted. With her earnings, she purchased school supplies for her children and paid for the marriage of one daughter.

The results seem small. One woman, one girl, a new family formed, one village at a time. But they are driven by the same great desires for our children we all share as parents. “We hope our daughters will be able to live their own lives,” another man tells us.